Love thy neighbour…

(And Thy QLD Retirement Village Scheme Operator)

The importance of ‘loving your neighbour’ has long been instilled in us. Whether it’s from the biblical heritage in the Book of Matthew, the television show by the same name that ran for eight seasons in the 1970s or just some good old-fashioned values – there is no avoiding the reality that good neighbourly relations is not only nice, it is an ideal that will elevate us and, by extension, elevate our communities.

With this in mind, surely there would never be a dispute, a conflict or tension, and definitely never a need to have laws in place to regulate the conduct of residents and Operators. Right? Well… no. Conflicts, tensions, and disputes can be a fact of any community life, including life in villages, and Queensland has had laws regulating behaviour for over 6 years.

This article explores the laws, which were introduced as amendments to the Queensland Retirement Villages Act 1999 in 2017 to prescribe clear and enforceable behavioural standards for Operators, including their staff, and residents. Consequences of non-compliance with the laws will also be considered, with a view to understanding whether the legal measures are working and, more importantly, whether they are the answer.

What do Operators need to do?

The behavioural standards place obligations on Operators – as would be expected. Operators cannot restrict a resident having control over their own affairs, or exercising self-reliance in respect of personal, domestic or financial matters.

Example

Betty has chosen Green Care to be her home care provider, but the Operator has had a disagreement with Green Care management and has prohibited them from entering the village.

![]()

An Operator cannot make rules effectively banning Betty’s chosen home care provider from entering the village without additional justification.

However, the rules go further and arguably require Operators to ‘step in’ when some ‘resident to resident’ disputes arise. Specifically, Operators are required to take steps to ensure residents live in a harassment-free and intimidation-free environment, and must ensure that residents don’t interfere with the privacy, peace or comfort of other residents.

This is a massive departure from the previous industry approach to independent living. Although the precise boundaries of these new requirements are not yet judicially defined, it does appear very likely that positive Operator action will be required.

Example

Every night, one resident (Mavis) yells aggressively at her neighbour (Joan) to turn the TV down (which Joan does turn it up way too loud because of some hearing issues). The yelling goes for over 10 minutes a session, and makes Joan feel on edge. She is now afraid to leave her home.

![]()

The Operator has obligations to take steps to ensure Joan doesn’t live in intimidation, and also has obligation to take steps to ensure that Mavis’ comfort is not impacted by excessive noise. At the same time, the Operator is to respect the rights of both parties, who may wish to resolve the matter without interference. The matter if further complicated and intensified when other parties are considered, such as the impact on adjoining neighbours (and their peace and comfort).

Finally, it is arguable that a failure of the Operator to take steps to train its management to respond to the above scenario is, in itself, a breach of the behavioural requirements.

It is also relevant to note that Operators are required to give a complete response to any resident or former resident within 21 days after receiving a relevant enquiry. This doesn’t require an Operator to respond to matters that have already been ‘asked and answered’, or which do not involve the rights and responsibilities under a retirement village contract.

What do Residents need to do?

Good relationships require involvement from all parties, so it is unsurprising that there are responsibilities given to residents as well as Operators.

A resident of a retirement village must not unreasonably interfere, or unreasonably cause or permit interference, with the peace, comfort or privacy of another resident.

Example

John’s village have started preliminary consultation regarding the potential development of a very large green space area beside John’s unit. The development will impact him during construction, and will dramatically change his outlook moving forward. John is discussing his concerns with the Operator, and the conversation is going well.

The Chairman of John’s residents committee tells John that the proposed development is a “Committee matter” and that John will be doing himself and his village a disservice if he continues to try to ‘go it alone’. Every time John speaks to the Village Manager (which is usually about unrelated matters), he notices the Chairman appear from nowhere and then demands to know what they were talking about.

![]()

The Chairman is stepping outside the scope of the Committee, and is interfering with the peace, comfort and privacy of another resident.

This should be a matter of concern for the other members of the Committee and the Operator.

Residents are also required to respect the rights of the Scheme Operator (and its team) to work in an environment free from harassment and intimidation, and must not act in a way that adversely affects the occupational health and safety of the people working in or for the Village.

Example

Frank moved into the village 10 years ago with his wife June, who passed away about 12 months ago. He believes the Village Manager doesn’t respond quickly enough to his queries. He puts queries to the Village Manager about all sorts of things, and will follow up every few days. Each time he enquires it becomes a little more demanding. The Village Manager is respectful, sets timeframes for responses and does what she says she will do. But nothing seems to satisfy Frank.

Frank’s latest request is for the vaccination records and the working history of the gardener so he can consider whether the proposed expense attributable to the gardener for the coming financial year is reasonable.

![]()

This is a difficult situation. Residents are entitled to information, and the mere act of asking for it is not an offence. However, residents are not entitled to ask for personal information of an Operator’s staff or contractors. In addition, interactions must be respectful. Repeated requests in circumstances where the answers or timeframes have already been given may well result in a negative workplace outcome.

When behaviour by a resident or the Operator is not OK

As can be seen from the above examples, behaviour may not always meet the minimum standards prescribed by legislation. In these cases, the Retirement Villages Act provides a pathway for parties to consider. The process under the Act involves preliminary negotiations, mediation and, if unresolved, a Tribunal hearing.

This pathway has real merit, but can be problematic in circumstances where timing is important or there is inappropriate conduct.

While there are some exceptions to the pathway to recognise immediate harm etc, it is important to note that inappropriate behaviour can trigger other legal requirements and, with it, other legal solutions.

Examples of alternative approaches to address behaviour issues in villages

Qld Police: The Police have the power to take action against unlawful conduct. This may include stalking, nuisance, bullying, assault, dangerous driving etc. The Qld Police can be contacted at: Qld Police. The Policelink phone number is 131 444 (24 hours, 7 days).

Local Council: Local Councils have broad powers to investigate and enforce local laws which might cover things like pet ownership, unlawful structures etc. Qld Local Councils can be found at: Qld Local Government Directory

Dispute Resolution Centres: Dispute resolution centres offer free mediation services to help manage neighbourhood disputes without going to court. Centres can be found at: Dispute Resolution Centre

Specialist Mediation Services: There are services that offer ‘user pay’ mediation services offered by qualified and highly experienced senior living industry professionals, which can often result in excellent outcomes. Senior Living Mediation* is one such specialist service and can be found at: Senior Living Mediation

Legal advice: Legal advice can be obtained from a qualified lawyer. This enables residents and Operators to know their rights in a particular situation, but it can be expensive. Lawyers can be found at: Qld Law Society Lawyer Search There are also community legal centres as: Community Legal Centres

ARQRV: The ARQRV is the Association for Residents in Queensland. It offers a wealth of information and members can receive information about disputes. They can be found at: ARQRV

* In the interests of full disclosure, the author is a director of Senior Living Mediation

Can conduct in a retirement village really be more?

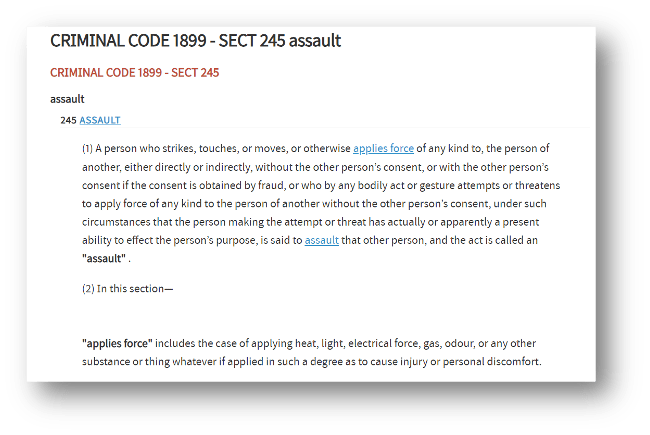

As noted above, conduct in can easily cross the lines, sometimes without parties knowing or intending it to do so. For example, conduct can be assault under the Criminal Code relatively easily. The Criminal Code defines assault as:

Example

Assault could include:

- Lifting a fist to someone in a threatening way

- Telling someone you will leave your TV on super loud all night if they don’t do what you want.

- Shining a torch in someone’s face.

- Touching someone in a threatening manner.

Of course, there are complexities and defences.

Can the laws work?

The Queensland laws require both residents and Operators to ‘respect the rights’ of those within the village. The concept of ‘respect’ being a legal requirement, rather than a fundamental and innate human value, might be seen as absurdly unnecessary or, at the very least, difficult to enforce. In fact, the very concept of regulating decency is vexed.

The questions being asked look like the following examples:

|

|

While it is beyond the scope of this article to answer these questions in depth, it is reasonable to conclude that penalty-based regulation can work – with varying levels of success, and that it is one of the best options we have been able to devise as a community.

Do the laws work – are they the answer?

How does one assess the effectiveness of the legislative requirements about behaviour in retirement villages? The obvious method of assessment might be to calculate how many breaches of these behavioural standards have been recorded as QCAT decisions, and to look at any resulting trends. Using this measure, the regulations would be an unmitigated success as there have been exactly zero published decisions regarding the provisions at the time of writing. However, the more accurate interpretation of that statistic is that there is no correlation between the effectiveness of the behavioural standards and the number of reported Tribunal cases. In fact, Tribunal case numbers have remained relatively consistent since the introduction, actually recording all time lows in 2018, 2019 and 2021, indicating that the lack of decisions is not an indication of the issues being faced at ground level.

Although there is a lack of comprehensive data, some preliminary indications can be drawn from the recent survey conducted by the Retirement Village Residents Association of the RVRA[1] by surveying over 1,259 residents in New South Wales retirement villages. The survey results showed:

- Over 40% of respondents experienced abuse;

- The types of abuse experienced include patronisation, harassment and intimidation;

- Abuse comes from other residents and the Operator;

- The abuse is not a ‘one off’, with many respondents reporting multiple events;

- The impact of the abuse of residents is significant, including some respondents considering self harm; and

- The response to the abuse included confronting the abuser, considering leaving the village, withdrawing from village activities and seeking help from others.

Although this is one survey in New South Wales, the results are sufficient to conclude that disputes are continuing to occur:

“It is a significant problem – resident against resident…It is horrific out there.” – Craig Bennett, President of the NSW Retirement Village Residents Association (RVRA)[2]

It appears likely that the behavioural provisions of the Act are not being used to their fullest extent by either Operators or Residents. Perhaps this is because neither party have confidence or knowledge to do so at this time.

Conclusion

Disputes occur in all forms of community living. The situation in retirement villages is unique because certain disputes can involve conduct that is actually ‘elder abuse’, which is not OK by any human or community standard. While there are a variety of solutions available to the parties involved, it appears that they are not often being utilised. In order to avoid escalation and to ensure that the retirement years of older Australians are enjoyable and everything they deserve, we need to ensure that the solutions are clear, available and accessible. The Retirement Villages Act outlines minimum behavioural standards to help address any situation, but they need to be communicated and understood. Once they become part of the village narrative, it is believed they will naturally thread through the fabric of the villages’ DNA. This will allow us to start to bring back better standards in the broader communities and, with it, achieve truly harmonious communities.

[1] https://www.rvra.org.au/news/news-articles/2023-06-15 accessed 27 August 2023

[2] https://www.theweeklysource.com.au/page/its-horrific-out-there-resident-on-resident-abuse-on-the-rise-in-retirement-villages accessed 27 August 2023.